"Music is the shorthand of emotion." Leo Tolstoy

Ivry GITLIS @ BEETHOVEN Kreutzer Sonata (complete) Martha Argerich, live 1999 http://youtu.be/DMHeTKCg3xc

Beethoven: Kreutzer Sonata (1. Adagio Sostenuto) - Martha Argerich & Gidon Kremer

Kogan plays Beethoven's Kreutzer Sonata (1/5)

Kogan plays Beethoven's Kreutzer Sonata (2/5)

The sonata was originally dedicated to the violinist George Bridgetower (1780–1860), who performed it with Beethoven at the premiere on 24 May 1803 at the Augarten Theatre at a concert that started at the unusually early hour of 8:00 am. Bridgetower sight-read the sonata; he had never seen the work before, and there had been no time for any rehearsal. However, research indicates that after the performance, while the two were drinking, Bridgetower insulted the morals of a woman whom Beethoven cherished. Enraged, Beethoven removed the dedication of the piece, dedicating it instead to Rodolphe Kreutzer, who was considered the finest violinist of the day. However, Kreutzer never performed it, considering it "outrageously unintelligible". He did not particularly care for any of Beethoven's music, and they only ever met once, briefly.

Moiseiwitsch and Heifetz play Beethoven Kreutzer Sonata Pt. 3/4

Moiseiwitsch and Heifetz play Beethoven Kreutzer Sonata Pt. 4/4 ·

http://youtu.be/yP9MpDfFz-cSources suggest the work was originally titled "Sonata mulattica composta per il mulatto Brischdauer [Bridgetower], gran pazzo e compositore mulattico" (Mulatto Sonata composed for the mulatto Brischdauer, big wild mulatto composer), and in the composer's 1803 sketchbook, as a "Sonata per il Pianoforte ed uno violino obligato in uno stile molto concertante come d’un concerto".

Kogan plays Beethoven's Kreutzer Sonata (4/5)

Kogan plays Beethoven's Kreutzer Sonata (5/5)

The Kreutzer Sonata (Russian: Крейцерова соната, Kreitzerova Sonata) is a novella by Leo Tolstoy, published in 1889 and promptly censored by the Russian authorities. The work is an argument for the ideal of sexual abstinence and an in-depth first-person description of jealous rage. The main character, Pozdnyshev, relates the events leading up to his killing his wife; in his analysis, the root cause for the deed were the "animal excesses" and "swinish connection" governing the relation between the sexes.

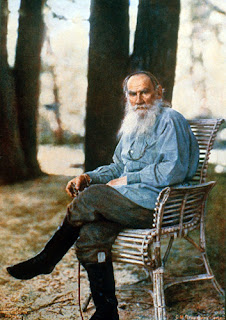

In an essay entitled “The Lesson of The Kreutzer Sonata”, Tolstoy (photographed here in 1908) explains his view of the subject matter. Regarding carnal love and a spiritual, Christian life, he points out that not Christ, but the Church (which he despised and which in turn excommunicated him) instituted marriage. "The Christian's ideal is love of God and his neighbor, self-renunciation in order to serve God and his neighbor; carnal love – marriage – means serving oneself, and therefore is, in any case, a hindrance in the service of God and men".

Of course, his religious viewpoints evolved over several years and might stem from the summer he began reading Schopenhauer in the late-1870s, while in the midst of writing Anna Karenina, a conversion he then shared with the character Levin. In 1882, he published “A Confession” which documented many of his new-found ideas, rejecting many traditional religious and social viewpoints.

Tolstoy, completing The Kreutzer Sonata in 1889, found himself confronted by controversy when attempting to publish it. However, the book also ran into problems in the United States in 1890 when the United States Post Office prohibited the mailing of newspapers containing serialized installments of The Kreutzer Sonata, a decision later confirmed by the U.S. Attorney General.

The New York Times reported in August, 1890, that four street vendors were “captured” by a New York City 1st Precinct policeman with cartfuls of “mutilated paper-covered reprints” of Tolstoy’s banned novel, admitting they’d received them from a “Barclay Street publishing house” and hawking them with the sign “Suppressed” in order to attract potential buyers’ attention. The judge at their hearing was told by the prosecuting attorney that this book “came within the category of indecent literature,” showing the judge a specially marked copy with specifically marked passages. Justice White, in the Tombs Police Court, apparently found “nothing likely to affect public morals” and felt the peddlers’ offense (“if any had been committed”) was misleading the public by “parading the book as a suppressed publication.” The peddlers and the publishers were then summoned for a further appearance. Apparently, the case went on to the Common Pleas Court No. 4 in Philadelphia where, on Sept. 24th, 1890, Judge M. Russell Thayer ruled that Tolstoy’s novel, The Kreutzer Sonata, was not obscene.

He was quoted in the New York Times that day as stating in his opinion “the book is a novel, possessing very little dramatic interest or literary merit. There is nothing in this book which can by any possibility be said to commend licentiousness, or to make it in any respect attractive, or to tempt any one to its commission. On the contrary, all its teachings paint lewdness and immorality in the most revolting colors. Nor is there any obscenity or indecency in the language used or in the story told, however it may offend a refined taste. It undoubtedly teaches the doctrine… that celibacy is better than marriage and a higher and purer state of being. And that it is the idea of a perfect Christian life, to which all Christian men and women should aspire. This strikes us, of course, as being very absurd and ridiculous, and as being opposed alike to Christianity and to the best interests of society. It may even seem to us to be the product of a diseased mind, yet the doctrine is by no means new in the world. The same idea was prevalent among many of the early Christians, who looked upon marriage as one of the consequences of the fall, and regarded it as has been said by a writer upon this subject as a tolerated admission of an impure and sinful nature.”

The Judge continues, “the hermits and anchorites of the early Christian times considered abstinence from marriage and from all sexual commerce as the triumph of sanctity and the proof and means of spiritual perfection. Modern Christianity, with cleaner and more sensible view of the subject, while it denounces licentiousness, looks upon marriage as a divine institution. Roman Catholics regard it with the veneration of a sacrament, and all Christian sects see in it an institution which lies at the foundation of all civilized society. Count Tolstoi’s ‘Kreutzer Sonata’ may contain very absurd and foolish views about marriage. It may shock our ideas of the sanctity and nobility of that important relation, but it cannot on that account be called an obscene libel. There is no obscenity in it. On the contrary, it denounces obscenity of every description on almost every page. Nor can the language in which he expresses his ideas be said to be in any proper sense obscene, lewd or indecent. It is not against the law to print or sell books which contain ideas and doctrines upon religious subjects which conflict with and are contrary to the orthodox teachings upon the subject. Every man has the right under such a government as ours to discuss such questions, either orally or in print, if he does so in a proper and becoming manner, and does not in doing so violate the decencies of life. He may call in question and argue against any received doctrine of the Christian faith, if he uses in doing so proper and becoming language but if one should introduce into such a discussion blasphemous language or ideas, or obscene, lewd, or indecent thoughts or words, or should make his description the occasion for reviling and scoffing at the most sacred things, or speaking of them in a profane, abusive, or indecent manner, he would unquestionably be liable to be indicted and punished therefor."

“But a careful and critical reading of the whole book has clearly convinced us that it is not liable to the charge of either obscenity or indecency. On the contrary, as we have already said, its whole purpose and scope is to denounce those vices in the severest manner. The fact that the author in discussing the question of marriage has come to some silly and very absurd conclusions, opposed alike to what is ordinarily conceived to be the Christian doctrine on the subject and the general opinion of civilized societies throughout the world, does not make its publication or sale a violation of the law. The work may be offensive to our opinions and convictions, just as others are which are daily sold in our book stores without objection or challenge from anybody, but it cannot be justly said to be of an obscene or lewd character; nor is it either in its sentiments or language in any degree calculated to minister to corrupt or licentious practices or to gratify lewd desires, or to encourage depravity in any form.” Judge Thayer’s concluding statement is: “The court was reminded upon the argument that the Czar of Russia and the Post Office officials of the United States have condemned this book as an unlawful publication; that the former has prohibited its sale within his dominions and the latter has forbidden its transmission through the mails. Without disparaging in any degree the respect due to these high officials within their respective spheres, I can only say that neither of them has ever been recognized in this country as a binding authority in questions of either law or literature.”

That did not stop Theodore Roosevelt, then a member of the United States Civil Service Commission, from calling Tolstoy a "sexual moral pervert."

Though Janáček first began working on a string quartet – and then a piano trio – inspired by Tolstoy’s Kreutzer Sonata in 1908, it wasn’t until 1923 that he actually composed the quartet we know by that name. Between those years, his own marriage deteriorated and they had already agreed to a mutual “in-house” separation before the composer met Kamila Stösslová in 1917.

"I was imagining a poor woman, tormented and run down, just like the one the Russian writer Tolstoy describes in his Kreutzer Sonata", Janáček confided in one of his letters to his young friend Kamila Stösslová. In the music of the quartet is depicted psychological drama containing moments of conflict as well as emotional outbursts, passionate work rush towards catharsis and to final climax.

Leoš Janáček - String Quartet No. 1, 'Kreutzer Sonata' (1 of 2)

“They played Beethoven’s Kreutzer Sonata,” he continued. “Do you know the first presto? You do?” he cried. “Ugh! Ugh! It is a terrible thing, that sonata. And especially that part. And in general music is a dreadful thing! What is it? I don’t understand it. What is music? What does it do? And why does it do what it does? They say music exalts the soul. Nonsense, it is not true! It has an effect, an awful effect – I am speaking of myself – but not of an exalting kind. It has neither an exalting nor a debasing effect but it produces agitation. How can I put it? Music makes me forget myself, my real position; it transports me to some other position, not my own. Under the influence of music it seems to me that I feel what I do not really feel, that I understand what I do not understand, that I can do what I cannot do. I explain it by the fact that music acts like yawning, like laughter: I am not sleepy but I yawn when I see someone yawning; there is nothing for me to laugh at, but I laugh when I hear people laughing.

“Music carries me immediately and directly into the mental condition in which the man was who composed it. My soul merges with his and together with him I pass from one condition into another, but why this happens I don’t know. You see, he who wrote, let’s say, the Kreutzer Sonata – Beethoven – knew of course why he was in that condition; that condition caused him to do certain actions and therefore that condition had a meaning for him, but for me – none at all. That is why music only agitates and doesn’t lead to a conclusion. Well, when a military march is played the soldiers march to the music and the music has achieved its object. A dance is played, I dance and the music has achieved its object. Mass has been sung, I receive Communion, and that music too has reached a conclusion. Otherwise it is only agitating, and what ought to be done in that agitation is lacking. That is why music sometimes acts so dreadfully, so terribly. In China, music is a State affair. And that is as it should be. How can one allow anyone who pleases to hypnotize another, or many others, and do what he likes with them? And especially that this hypnotist should be the first immoral man who turns up?

“It is a terrible instrument in the hands of any chance user! Take that Kreutzer Sonata, for instance, how can that first presto be played in a drawing-room among ladies wearing low-necked dresses? To hear that played, to clap a little and then to eat ices and talk of the latest scandal? Such things should only be played on certain important significant occasions, and then only when certain actions answering to such music are wanted; play it then and do what the music has moved you to. Otherwise an awakening of energy and feeling unsuited both to the time and the place, to which no outlet is given, cannot but act harmfully. At any rate that piece had a terrible effect on me; it was as if quite new feelings, new possibilities, of which I had till then been unaware, had been revealed to me. ‘That’s how it is: not at all as I used to think and live, but that way,’ something seemed to say within me. What this new thing was that had been revealed to me I could not explain to myself, but the consciousness of this new condition was very joyous. All those same people, including my wife and him, appeared in a new light.

“After that allegro they played the beautiful but common and unoriginal andante with trite variations and the very weak finale. Then, at the request of the visitors, they played Ernst’s Elegy and a few small pieces. They were all good, but they did not produce on me a one-hundredth part of the impression the first piece had. The effect of the first piece formed the background for them all.”

Tolstoy: The Kreutzer Sonata – translated by Aylmer Maude.

Δεν υπάρχουν σχόλια:

Δημοσίευση σχολίου